Physician Burnout – Should We Worry?

When studying the symptoms of burnout among physicians and mental health workers in the 1970s, Herbert Freudenberger, a German-American psychologist, coined the term “burnout.” In 2017 Health and Human Services (HHS) described professional burnout as an occupational hazard that could lead to high-quality healthcare professions leaving the practice of medicine. By 2017 physicians reporting frequent or constant feelings of burnout totaled 51%–up from 40% in 2013.

The Center for Treatment of Anxiety and Mood Disorders reports that physician burnout is growing in the U.S. with one in three physicians experiencing physician burnout at any point in time. Compared to other professions, physicians are 15 times more likely to experience burnout. About 45% of physicians report that they would quit the profession if it weren’t for the money, and approximately 400 physicians commit suicide each year. Those numbers emphasize the need to quickly address the burnout issue.

Physician burnout symptoms seem to mirror symptoms of other stress disorders, but there are also distinct differences. Dr. Dike Drummond, author of the blog “The Happy MD,” talks about physician burnout in his article “Physician Burnout and the Four Phases of Compassion Fatigue” (blog post #297) when he says, “Losing the ability to feel empathy, sympathy and compassion for your patients is a constant risk for all of us.”

Physician Burnout Symptoms might include:

- Physical and emotional exhaustion that leaves you “worn out” and unable to recover during downtime

- The development of a cynical and negative attitude regarding work and patients

- A reduced sense of purpose along with a feeling that what you’re doing has little to no meaning or value

Ashley Altus, a writer for The DO, a publication of the American Osteopathic Association (AOA), reported on Dr. Octavia Cannon’s talk to the January 25, 2018, AOA LEAD (Leadership, Education, Advocacy & Development) Conference in Austin, Texas. Dr. Cannon challenged physicians to teach students and residents about the importance of life outside of medicine. “Remind them of the importance of empathy,” Dr. Cannon said. “Encourage them to take time for themselves.”

Dr. Cannon continued to discuss how distress for young physicians is at its peak during training in medical school and residency, citing Medscape’s 2018 National Physician Burnout and Depression Report in which data suggested that 42% of physicians reported symptoms of burnout. Ms. Altus reported on 5 key takeaways.

- The highest rates of burnout occur in critical care medicine, neurology, family medicine, OB-GYN, and internal medicine.

- The lowest burnout rates appeared in the specialties of plastic surgery, dermatology, pathology, ophthalmology and orthopedics.

- More than 50% of physicians who felt burned out noted that a contributing factor was that they had too many bureaucratic tasks, i.e., charting and paperwork.

- Patient care suffers when physicians suffer from depression. Approximately one-third of physicians reported that due to depression, they are easily exasperated and 32% reported that they were less engaged with patients.

- About 50% of physicians reported that they cope with burnout through exercise while about 46% talked with family members and close friends and about 42% coped by getting more sleep.

Physicians are split on possible solutions to burnout. Reducing financial stress by increasing compensation was favored by about 35%; about 31% favored more manageable work schedule/call hours; and about 27% felt that decreased government regulation would be the most popular suggestion.

Senior News Writer for the American Medical Association Sara Berg suggests that medical students might consider the inherent or potential stressors of a specialty as part of their decisions about the specialty they want to practice. In a recent survey about burnout and depression, more than 15,000 physicians from 29 specialties provided responses indicating that 42 percent of respondents were burned out, which was down from 51 percent the prior year. The rates of burnout among medical specialties are shown below:

- Critical care: 48 percent

- Neurology: 48 percent

- Family medicine: 47 percent

- Obstetrics and gynecology: 46 percent

- Internal medicine: 46 percent

- Emergency medicine: 45 percent

Addressing Physician Burnout

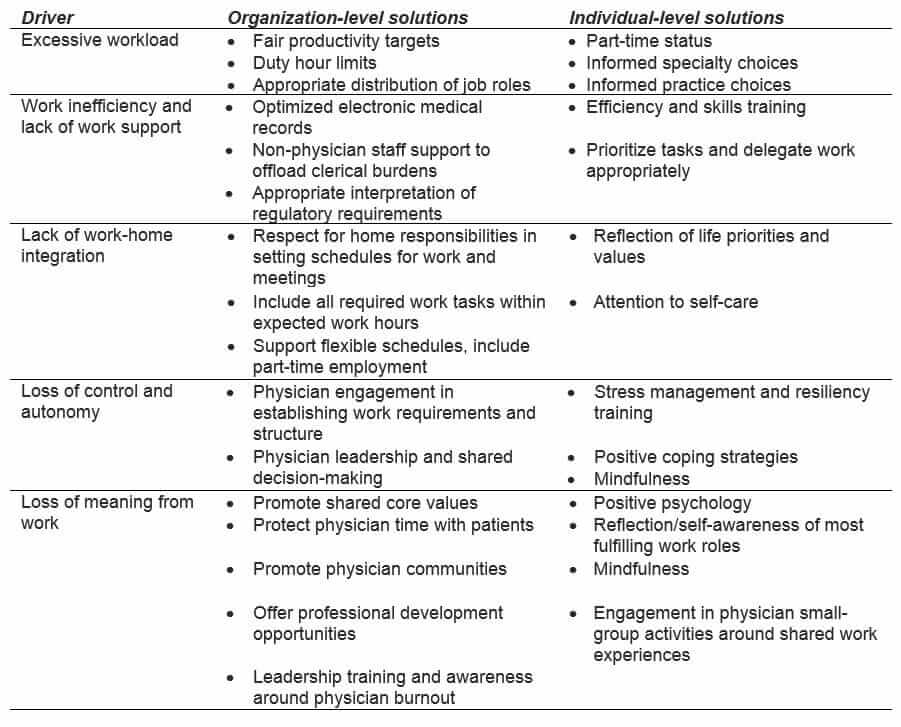

The Journal of Internal Medicine article, “Physician Burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions,” by C.P.West, L.N.Dyrbye, and T. D. Shanafelt, offer some insight to the causes and possible solutions to physician burnout and suggestions to help alleviate physician burnout. Physicians list the top stressors to be bureaucratic tasks, heavy workloads, computerization, and working around the clock. The authors’ list of common drivers and selected solutions for physician burnout is reproduced below:

In their article for Emory University’s GME program, Adams and Loftus discuss steps that the university‘s GME program, the seventh-largest GME program in the country, has taken to prepare future physicians. Highlights of the Emory program are very briefly summarized below.

Pay Attention: Stress often takes a silent toll. Physician wellness improvement programs can be implemented at worksites.

Fill the Tank: Stress is cumulative and must be managed early and continually. Ensure that staff takes time for meal breaks; makes priorities of time with family; vacations and exercises; eats properly; and sleeps sufficient hours to restore the body and mind.

Boost Empathy: Ensure that psychological and/or spiritual support is available for physician and nursing staff when disasters (big and small) happen. Adams and Loftus offered this from George Grant, a psychologist and theologian, “A major cause of physician stress and burnout is ‘empathic’ imbalance. Most clinicians, to devote the fullest attention to patient and program, are taught to suppress their own concerns and feelings.”

Champion Wellness: Just as physicians tell patients to eat better, exercise, quit smoking, and find healthy ways to relax, the message needs to be passed along to other physicians and medical colleagues.

Strengthen Compassion: Research has proven that “compassion” is not an inborn trait. It can be taught and strengthened through instruction.

Restore Joy: The Blue Ridge Academic Health Group report, an annual publication, stated in one of its recent publications: “We pay a staggering cost in lost productivity, risks to mental and physical health, eroding quality and safety, diminished patient satisfaction, staff turnover, and lost dollars. At the extreme [is the] personal toll of depression and suicide….When joy is lacking and burnout is present, the stakes are high.”

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has also published a whitepaper on a framework for improving “Joy in Work.”